Women Writers in Eighteenth-Century Rome and the Accademia Degli Arcadi

Figure 1: Angelica Kauffmann, Portrait of the Impromptu Virtuoso Teresa Bandettini-Landucci of Lucca, 1794, oil on canvas, 50.47” x 36.85”, https://www.wikidata.org/wiki/Q67204120

During the Renaissance, Rome was the cradle of the Christian papacy, and the Church was the undisputed political power of the time. Rome was where the academies of the period first developed. At the time, the Church was interested in promoting the Italian peninsula's cultural importance to re-establish the relevance of ancient Rome's classical thought and culture, supporting this kind of association. The Roman academies were congregations of learned men (where women were mostly excluded) and not institutes for knowledge instruction. These associations typically gathered around a patron who circumscribed the interests to be discussed in its members' congregations. These interests could focus on different areas of knowledge such as science, arts, philosophy, literature, and religion. In this historical period, the academies were important sources of contemporary cultural discussions. The Accademia Degli Arcadi (Arcadian Academy), established in 1690, was the first academy to accept female members, forging a unique circumstance where a number of them became prominent writers. It was the Arcadian Academy who provided them with enough agency to reach a degree of serious literary production. Most notably, although still limited compared to male production, the extent to which they were published was an astonishing outcome. The Arcadia Academy was active for almost one hundred years and was marked by the leadership of three men: Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, Francesco Maria Lorenzini, and Michel Giuseppe Morei. Each of these three men had a distinct conception of the role of women in the academy. According to the level of support they provided, their tenures concluded in three contrasting outcomes for the female writers. Crescimbeni opened the doors of the academy to them, Lorenzini ignored them, and Morei allowed ample participation and broad support for female poets.

In addition to the role played by the Arcadia Academy in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and as compared to the other European geographical areas, the female literati were served by a more open role assigned to women in the Italian regions [1] in a period that coincided with the Grand Tour, an era of deep inspection and exploration of the Italian peninsula by foreigners.

The Grand Tour was referred to a period when Italy was widely visited by an elite coming from all corners of Europe, a custom of the aristocracy to be exposed to the arts of classical antiquity and the Renaissance, and a journey that constituted an essential educational rite, especially, but not exclusively, for European men. The tolerance granted to women in the Italian regions provided them with a certain space of inclusion in the intellectual spheres. This was a peculiarity that conveyed the thriving of learned and aristocratic women who affirmed their independence from local and European traditional customs and beliefs, and particularly of being relegated exclusively to the home domain. In the Italian peninsula of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this tolerance facilitated the prominence of a number of women in literature, science, publishing, and to a lesser degree, painting. Their incorporation into society was distinct and more involved in the public and cultural dimensions than in other places in Europe, a fact visible to all visitors of the Grand Tour.

It is important to notice the relevance of this episode of Italian female intellectual history since it represents a proto-modern sample of how women in this part of Europe were establishing a place of involvement outside the home, singularly displaying their intellectual and creative capabilities. However, as exemplified by the history of the Arcadian Academy, women needed to be given a platform by their male counterparts to sustain their presence in the cultural realm. When women were deprived of such privilege, their work receded into obscurity or simply vanished. The account of this portion of the history of Italian women writers highlights how throughout history, women had to earn the support of their male counterparts to grant them their introduction and place in society.

However, the history of the Italian female writers of the eighteenth century had precedents and emerged after a series of interrupted developments. It was advanced by special circumstances occurring in Italy in previous times and contemporaneous events to their restrained emancipation. The particularities of the contextual situations to the advent of Italian women intellectuals include a historical background of women writers of the sixteenth century, a brief account of the era of the Grand Tour, and the context of Italian women's participation in society at large. This sets the stage to understand the history of the Arcadia Academy and its female presence, elucidating how these special conditions acted as a fertile ground for women's groundbreaking cultural involvement. Finally, the essay will conclude with how the characteristics of improvisational poetry made the female literary production vanish. On the opposite side, the recount of a small but outstanding collection of books, the Consul Smith Library [2], where many female Italian writers of the eighteenth century were represented, highlights an exceptional historical legacy of Italian female writers’ production.

Historical Background of Italian Women Writers

In the late seventeenth and the eighteenth century, during the Grand Tour era, the Italian peninsula turned into a region profoundly scrutinized by a continuous crowd of visitors. In Europe at the time, women were still confined to the home, rarely traveled, and were always accompanied by parents, brothers, husbands, or sons. These customs kept them away from the cultural domain and the practice of cultural activities. Italy was not an exception. However, women there enjoyed an opening into these spheres that was more hospitable than in other places in Europe. Additionally, as will be discussed further in this essay, the academies provided an alternative to convent life to access knowledge [3], and constituted a bridge for women to introduce themselves into a territory mostly barred from them.

The greater Italian female participation in their society and the prominence of women literati during the eighteenth century was a build-up through previous centuries, a crucial fact for what was to come to fruition later during the era of the Grand Tour. For Italian women, female writers of the sixteenth century would become the stepping-stone and prime reference at the beginning of the eighteenth century. To elucidate this phenomenon, we need to go back to the Middle Ages, when education was not easily available to women. It was considered dangerous, and its access was full of restrictions and well-defined norms. In passages of On the Government and Behavior of Women by Francesco da Barberino (1318-1320), the author described some of the intricacies involved when he asserted that women’s education was only recommended for ladies of the high aristocracy, cautioning that education would enable them to be rulers of land and people. He also stated that education for the rich and powerful bourgeoisie daughters was acceptable, providing that the fathers be in charge of that decision. As for poorer women, education was not advisable unless they were predestined to the convent [4]. These ideas about women’s education constituted a regimen of beliefs under which women lived for centuries, but against which women in Italy—first in the sixteenth century and then more successfully in the eighteenth century—were able to break through albeit to a limited extent [5].

More than a century and a half before the establishments of academies in Rome in the late seventeenth century, and despite educational restrictive circumstances, there are important accounts of women's active literary participation in the Italian peninsula. These events are a testimony to the existence of precedents for the female literary presence during the early Italian Renaissance. In the late fifteenth century, Italian society had been shaken by some distressing experiences that had reshaped the fabric of society. The key event that triggered a succession of changes was the Italian peninsula invasion by Charles VIII, King of France in 1494, which ravaged towns and the countryside. Such developments led to the displacement of the population into urban centers, triggering the mixture of social classes, new codes of behavior, and the collision of new opportunities, resulting in women becoming highly visible in society. They had a prominent presence in the lives of rulers, courtiers, and members of the clergy, especially in the most prominent cities of the peninsula, such as Rome, Florence, and Venice. In many cases, women in certain courts of these city-states had a more active role than women in other European regions, asserting their influence through men of power that saw them naturally fit as diplomatic figures, especially in disputes and negotiations.

In the broader cultural arena, special conditions paved the way for increasing female literary involvement. In the sixteenth century, literature was made more accessible to a wider public, and the female character was gaining mythical significance, conditions from which women writers yielded fruitful advantages. It was a time when classical education was replacing religious upbringing with a predilection for secular literature. Simultaneously, the publishing industry in the Italian regions was reaching the pinnacle of its development, and readers and authors were no longer part of an elite but were part of a wider segment of the population. This new readership, of which females were an important part, had a marked preference for poetic work [6]. These lyrical productions exhibited an inclination towards the imitation of the poet Petrarch (1304-1374), the creator of the Italian language model, and Renaissance lyrical poetry. In doing so, this type of poetic work fostered the popularization of the Platonic creed in which the female figure was perceived as an earthly symbol of the divine, in the sense that a man's love for a member of the opposite sex was seen as the first step to reach divinity [7]. The female writers utilized the above-described conditions to their advantage, highlighting the admired female figure through their poetry. That way the Petrarchan-Platonic model became a principle upon which literary women transformed themselves from inspirers into producers of poetry.

Italian female writers officially entered the literary scene in the sixteenth century, although their prominence was interrupted and short-lived. The period between 1538 and the end of the century became a singularly advantageous one for them. As a testimony to their important literary production, after 1538 [8], two hundred books were either authored by women, were anthologies where women were included, or were men's publications in which women participated [9]. However, after 1557, the censorship of the Inquisition greatly diminished the number of women's participation in literary publications. By 1559 women's destiny dramatically changed once again when political struggles and economic depression brought their literary creations almost to a halt. The ensuing scarcity brought up by these events prompted, being deprived of dowry, countless upper-class unmarried women to be sent to live in the convents—many of them from birth. As a testament to their adversity, a limited number of female literary figures narrated the difficulties imparted onto those without a religious vocation, denouncing the injustice they endured [10].

In the eighteenth century, after approximately one hundred and fifty years of limited presence in literature, the fate of female literary work changed with the establishment of academies all over the Italian peninsula. The Arcadian Academy became one of the most important repositories among them when some of the male leaders of these academies began to provide means for women's participation. At the origin, the promise of a united Italy was the underlying goal of the founders of the Arcadia Academy, Giovani Maria Crescimbeni and Gian Vicenzo Gravina, his most important partner. The cultural project of the academy was the creation of a Roman institution with the ultimate goal of inducing the integration of the Italian peninsula's literary community. To accomplish such an ambitious cultural vision, they needed to be inclusive to build the broadest possible base for which they devised a scheme that was a complete cultural breakthrough at the time: they bridged together both social strata and gender. Consequently, with an eye on opening their doors to a broader population integrating class and gender, they facilitated the increasing female presence in these institutions. Additionally, thanks to its founders' guiding principles, the Arcadian Academy concentrated its practice around the stylistic pastoral principles, advocating for simplicity, clarity, purity, and restraint, inspired once again by Petrarchism, a direct fortuitous genealogy to women writers of the sixteenth century we alluded above. However, this advocacy was chosen as a counterpoint to the baroque taste of the late Renaissance, which was deemed flamboyant for favoring "its taste for rhetorical artifice and its emphasis on wit and wordplay,” [11] which the founders of the Arcadian Academy disdained for its artificiality, phoniness, and lack of honesty and truth.

Created in Rome, the Arcadian Academy proliferated to many cities and was so prosperous that there were fifty-six Arcadian colonies dispersed throughout the Italian regions by the mid-eighteenth century. Its founders successfully achieved enough prestige for the institution, becoming an ambitious goal for any poet and writer—male or female—to be affiliated with it. As a collateral result, the female literary production grew and expanded, although always linked to their male counterparts' acceptance. The majority of the Arcadian Academy women wrote poetry, but several also produced comedies, tragedies, dialogues for musical accompaniments, and librettos [12].

The tracing of this part of female Italian writers’ history establishes a firm lineage between those of the sixteenth century and those of the eighteenth century—united by their common stylistic interest in Petrarchism and lyrical poetry. Before unearthing the advancements of female literati in the Italian Peninsula in the eighteenth century, further background information about the cultural context in which they were involved will be addressed, particularly in what relates to the era of the Grand Tour and the scope of Italian women’s presence in their society at large.

Figure 2: Angelica Kauffmann, Portrait of a Lady, C. 1775, oil on canvas, 31.18” x 25”, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/kauffman-portrait-of-a-lady-t00928

Italy’s Historical Background in the Era of the Grand Tour

From a broader perspective, the era of the Grand Tour facilitated the exhibition and scrutiny of every angle of Italian society by the foreign visitor, and one finds proof that women's place in the society of the Italian peninsula was distinct from every other European region in the unmistakable reaction of the tourists towards them.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Italy was not a nation but a collection of regional states, each with a city that was central to that region's identity. These regions coalesced under linguistic and cultural geographical boundaries that had a diversity of political and economic arrangements. The Italians at that time did not have a sense of a larger national identity. Italy was then a geographical entity and not yet a political one. However, the era of the Grand Tour was going to play an essential role in the nascent sense of Italian integrity. With their gaze and judgments, the foreigners gave back to the citizenry of the regions a much more cohesive view of themselves than what they could have ever been able to perceive on their own. Under this state of affairs, during the eighteenth-century, tourists from all over Europe went in large numbers to visit Rome and all the most important Italian cities, like Venice, Florence, and Naples. For the foreigners, the Grand Tour was an itinerary, a journey to visit all the important cities and absorb all aspects of their culture. Visitors—especially male visitors—went to Italy to complete their education, which was an essential precondition to be a "citizen of the world." Tourists went to Italy to view the remnants of its glorious Roman past but also to view its architecture, palaces, libraries, and museums in addition to its theaters, opera houses, musical performances, coffeehouses, casinos, and salons.

At the time, Rome was a city of antiquarians, clergymen, poets, and aristocratic salon ladies whose primary interests were in asserting their social prominence through cultural affiliations. The visitors' observations and attention brought about consequences in the Italian society, sometimes reinforcing phenomena that the locals had no particular interest in. Within this framework, travelers were acutely interested in a singular characteristic of Italian society: their women's participation in the public domain and realm of culture, and they were particularly enticed by encountering learned Italian women. Women were seen in public spaces, in salons, in academia, in the theater, and the opera. The prominence of women in the intellectual and cultural life of many cities in Italy was still a novelty, and foreigners went there to experience that phenomenon firsthand: "Like the churches, galleries and Roman ruins, women, were monuments to be admired and critiqued.” [13]

Figure 3: Fra Galgario (Giuseppe Vittore Ghislandi), Portrait of a gentlewoman with a fan, 1710, https://history-of-fashion.tumblr.com/post/124764066354/1710-fra-galgario-giuseppe-vittore-ghislandi

During the Era of the Grand Tour, Italian women had conquered a place in society which no other group from any other geographical area in Europe had yet achieved. They actively shook up the conventional role of their gender within society and, most importantly, forged a secure place in the arts and sciences. They were pioneers in revealing the intellectual and the artistic persona within their gender.

Larger Context of Women’s Participation in Society

As already discussed, visiting Italy, the typical northern European foreigner would notice distinct and contrasting differences in women's behavior and their way of life, habits, etiquette, and attitudes when comparing them to their place of origin. Some of these customs put women in the spotlight and under special circumstances to their advantage. The curiosity manifested by foreigners directed the public attention on them, exalting their presence and notoriety. Nonetheless, for their unconventional ways, the foreigner built a stereotyped assessment of Italians. They undoubtedly admired their culture but thought of them as politically and religiously corrupted, morally permissive, and lacking ambition, characteristics that they alleged were attributed to the warm Mediterranean climate [14]. This general assessment given by foreigners spoke to a certain behavioral indulgence from Italians that could explain some of the liberties acquired by Italian women, freedom that profoundly impacted their quest for cultural participation.

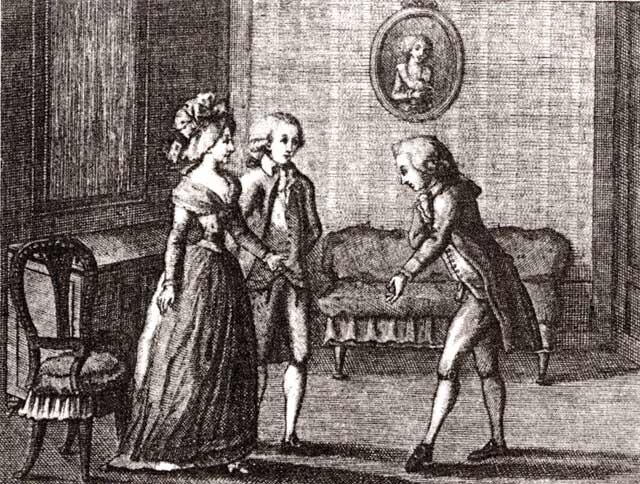

The social eccentricities observed by non-natives not only pertained to the female gender—however, these conditions aided in bringing women into focus. What caught the attention of these foreigners was what they perceived as the corruption of Italian morals seen in their behavior, their lack of a clear definition of gender roles, and the overlapping of some of them. The attraction and fear of sexual ambiguity were at the heart of the lack of understanding of Italian cultural differences [15]. Among the most astonishing characters, unique to Italian culture, were the castrato and the cicisbeo. On the one hand, the castrato was a feminized male opera singer with a soprano, mezzo-soprano, or contralto voice, which resulted from castration before puberty. On the other hand, the cicisbeo was a young gallant that would accompany aristocratic married women to all social occasions in place of their husbands [16]. The former could sometimes cross-dress, and the cicisbeo was probably no doubt a curiosity that animated the most controversy among foreigners for their public display of what was considered immoral and improper, suggesting out of the norm societal demeanors. Nevertheless, the cicisbeo was essential to some aristocratic women to be able to circulate the city accompanied by a male, expanding their radius of influence, social contact, and access to culture, affording them more freedom, especially when the husband was occupied with his mistress, a common incidence at the time.

Figure 4: Il Cicisbeo, https://www.venetostoria.com/?p=5889

Figure 5: Luigi Ponellato, Il Cicisbeo, illustration from an edition of Carlo Goldoni's theatrical works, 1790, https://www.wikiwand.com/fr/Sigisbée

Women in the Italian peninsula were challenging the notion that their place was inside the home and occupied only in housework and did not seem to observe other communities' typical rules in Europe [17]. The prominence of women in the intellectual culture of Italian society was unmistakable: they were present in the streets, in opera houses, in theaters, in salons, and more. Nonetheless, what was most remarkable is that Italy acquired a reputation for having more "learned ladies" than any other European nation during the period of the Grand Tour. Italian women's outstanding achievements in science and the humanities were observed throughout the Italian peninsula, resulting in the Italian regions' fascination with its distinguished women writers, poets, scientists, journalists, and philosophers. They were considered the living expressions of the greatness of each city, a peculiarity that marked a difference against foreign approaches [18]. Italian had no trouble exalting their female luminaries turning them into poles of attraction.

Seeing women performing important participatory roles in realms commonly assigned only to men was particularly unsettling for international Grand Tourists. Despite that the eighteenth century was a critical moment for the reassessment of traditional gender roles all over Europe, in Italy, this interest had distinct characteristics. A flourishing salon culture persisted in the region, where the subjects focused on the creative arts. However, the educated elites in Italian society were also debating women's nature, debates in which remarkably, women also participated [19]. That distinctiveness in Italy marks an initial phase of the modern conception of women's roles, and Italy acted as a living laboratory, shedding light on what women's capacities really were.

The Arcadia Academy

In the previous sections, we unearthed some special historical and societal conditions that explained the remarkable particularities of Italian female interactions in society at large and the cultural sphere in particular. To a certain extent, these special qualities paved the ground for the unique history of literary women in the Italian regions. However, although intricately related to either the acceptance or restrictions of its consecutive leaders, the Arcadian Academy was responsible for providing them with a relevant platform for a significant evolution of women's literary production of the era. In the sections that follow, the history of the organization and the unique circumstances that resulted in the emergence of the women literati will be discussed.

Created in Rome in 1690, the Arcadian Academy wanted to improve society and promote the common good. It was established in opposition to the Marinism era of poetry, also called Secentismo, the style exemplified by poet Gianbattista Marino (1569 – 1625). Extravagant and excessive ostentation was the common ground, and wordplay, exuberant descriptions, and beautiful musicality were predominant. In contrast, the Arcadians looked for a purer, simpler, and natural expression mode where the language was more important than the images that it created. The purposes of the Academy were to encourage the restoration of Italian preeminence in all matters of culture, including literature, scientific knowledge, music, and, to a lesser degree, the visual arts. Moreover, it was announced by its founders as the symbol for a new beginning in literature. The name Arcadia was a reference to the ideal mythological rustic place where simplicity and goodwill prevailed. Its style came to be known as the pastoral, the idealized version of country life, in which a mindset was central to exercising the arts. It meant the artist could identify with the simple way of life of the countryside, enjoying the natural beauty, taking satisfaction with only a little, endorsing moral affiliations such as friendship, hospitality, wisdom, simple piety, and devoting themselves to poetry and peace [20].

Figure 6: Sébastien Bourdon, “Christina of Sweden on Horseback,”1653, 12.5’ x 114.5”, Museo del Prado.

The origins of the Arcadian Academy go back to the second half of the seventeenth century in Rome, and its precedents were associated with a foreign woman with a profound interest in literature and music, Queen Christina of Sweden. She was a strong-willed personality with a broad intellectual interest in the arts, sciences, and philosophy, more so than the monarchical role assigned to her by lineage. She had abdicated the Swedish throne, moved to Rome, and by her own will was confirmed a Catholic in the papal city in 1655 by Pope Alexander VII. Arriving there, Queen Christina surrounded herself with the Roman elite's most powerful and began an academy of literature and philosophy. With a group of intellectuals congregated under her patronage, they met for the first time on January 24, 1656. In continuation of that association, in 1674, she founded the Accademia Reale, a "conversation group" that included the most distinguished literary, political, and religious figures of the city, a congregation formed by mostly men. At their meetings, discussions ranged from philosophy, science, astrology, theology to poetry. In devising a list of rules for the constitution of the Academy, Queen Christina emphasized that music and poetry would be integrated into the gatherings. This aspect was carried out into the future Arcadian Academy and turn out to be critical for the development of literary production and the art of improvisational poetry within that institution, an art in which women later flourished. When Queen Christina died in 1689, the Arcadian Academy was founded by the same intellectuals present in her circle.

Figure 7: Nicolas Poussin, Et in Arcadia ego, C.1638-40, http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/poussin_nicolas.html

The pastoral mindset required a natural and inspiring environment to express its lyrical creations, referring to Arcadia, the mythical Greek place of ideal simplicity and innocence. Initially, there was no fixed meeting point, and the Arcadians congregated in various gardens around Rome, some of them with theaters explicitly designed for them. Arcadians officially assembled seven times a year, from May until October. However, members could also hold informal gatherings at any time. The first meeting of the Arcadian Academy took place at the monastery of San Pietro in Montorio. Subsequently, its congregations were held at the homes of various Arcadian patrons, including the former residence of Queen Christina of Sweden, the Giardino Riario Alia Lungara, the Duke of Parma's Orti Palatini, Francesco Maria Ruspoli's Giardino Su Monte Esquilino, the Farnese Gardens on the Palatine, and the Ginnasi garden on the Aventine [21]. The Arcadians called the various locations of their meetings Bosco Parrasio, meaning “Arcadian wood.”

Figure 8: Plan of Bosco Parrasio, the headquarters of Accademia dell' Arcadia in Rome, 1804. Source: Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, Storia dell'Accademia degli Arcadi istituita in Roma l'anno 1690.

As mentioned at the beginning of this research, the Arcadia Academy accepted members from all walks of life and genders, which is how women entered their circles. The enlisting of the Academy was broad, but the clergy, the most powerful elite at the time, was disproportionately represented. In line with the Arcadian Academy founders, the clergy was especially interested in the return of Italy's prominence in cultural matters and was sympathetic, as a tool for political gains, to the collaborative diplomatic function of the Academy.

In order to achieve cultural greatness, the Academy had a sharp focus on its literary vision. According to the ancients ' classical models, its purpose was to revive good taste ("buon gusto" in Italian) and restructure Italian drama and poetry. To preserve certain equality among the individuals and to attract innovation, during recitations, all members were disguised in imitation of the shepherds of ancient Arcadia, and they would call each other "Arcadian shepherds." When women began to be accepted into the ranks of the academy, presumably, the disguising would act as a shield to allow them a more participatory role, making them more acceptable in their somewhat concealed attire. Including female members in Arcadia was also a strategy to control culture by cultivating intellectual and social behavior [22] models to inculcate their desired notions into a larger segment of society.

Although women were integrated into the Arcadian Academy, restrictions applied to them, signaling that their status was scrupulously controlled. At most of the meetings, the Arcadians read their poetic works aloud, except for the Cardinals and women, whose works were recited by other Arcadians. On the other hand, one of the yearly meetings was reserved for reciting Arcadians' works which could not be present in Rome, and the work produced by its members was published in two multi-volume series: Le Rime Degli Arcadia and Le Prose Degli Arcadia [23].

Eventually, as mentioned above, the Arcadian Academy expanded beyond the city of Rome to incorporate other local groups, called colonies. This way, at the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Arcadian Academy in Rome began a wave of literary reforms throughout Italy, raising the number of opportunities for literary women to exercise their creative and intellectual capacities.

Arcadia Academy, its Phases, and Women’s Inclusion

The Arcadian Academy was the first Academy in Italy to include women as members. Although never in overwhelming numbers, women began to be included in this Academy because its leader had ambitious objectives for the Italian Regions. Central among them was the diffusion of good taste. To reach that goal, the Academy needed a broad audience. To make changes more effective, it needed to touch as many souls as possible, and therefore it opened its doors to beginners and dilettantes [24]. Under these precepts, women could not be ignored and began being welcomed into their congregations.

The Academy represented its female members in two distinct ways. First, as pastorelles or poets, whose accomplishments had to be as proficient and as meritorious of publication as their male counterparts and second, as nymphs who fomented diplomacy and knew how to entertain the upper classes [25].

The inclusion of female members was devised according to predetermined internal rules and did not happen from the start. From 1700 and on, Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, the founding member and first leader of the institution, explicitly changed the guidelines to include them. The female suitability for entry into the Arcadian Academy required that a woman be at least twenty-four, possess nobility, and appreciate, read, and practice poetry [26]. The women selected had certain common qualifications, all having aristocratic and influential backgrounds. They were already either poets or learned in the humanities, and their fathers or a special tutor typically had educated them. However, some acquired their knowledge through self-training. In the confined conditions under which women subsisted, those permitted to enter the Academy accounted for a meager fraction of them within the population.

In keeping with numerous regulations, there was only one path for women to get into the Academy, and a mere number of six memberships per year were allocated for them. They needed to be nominated before the Collegio, a small deciding body of the Academy, who produced a secret vote. To be designated as “acclaimed members,” a status generally conceded to heads of church and state, a small percentage of women were able to qualify and were almost always related to their aristocratic relevance. Among them were Queen Maria Casimira of Poland, Grand Principessa of Tuscany, Violante Beatrice of Bavaria, Ricciarda Gonzaga Cibo, Duchess of Massa and Carrara, and Giacinta Ruspoli Orsini, Duchess of Gravina and niece of Benedict XIII [27].

Figure 9: Author Unknown, Violante of Bavaria, Grand Princess of Tuscany, https://markfrm.blogspot.com/2014/10/13_13.html

Despite the openness afforded to them, limitations on women's action abounded. It is worth noting that just a few women participated in the foundation of Arcadian colonies, and none had consultative or leadership power, and in every Arcadia, the presence of women was met with caution and restraint [28]. Therefore, while women were allowed to be included, their participation as full members was extremely constrained and regulated. However, in Rome's clerical courts, the center of power in the eighteenth century, aristocratic women were allowed to offer their palaces as meeting places for official or unofficial gatherings, promoting their functions as diplomats when negotiations between parties were necessary. These women gained a considerable amount of influence using their salons to keep close alliances with the highest church officials and exercise their leverage in court business, interfering many times in politics in favor of their preferred alliance [29].

Arcadian Academy—Three Phases

The evolution of the Arcadian Academy from the beginning of the eighteenth century to its dawn by the end of the century is crucial to understanding the relationship between the Academy and the female genre, with its nuances and intricacies. The Academy went through three phases with its members in general and with its female affiliates in particular. These phases were the "Arcadia Prima," the "Arcadia Seconda," and the "Arcadia Terza," each of which was led by a single custode. The custode, or chief shepherd, was the top elected administrator, recordkeeper, and policy executer, shaping the character of the organization.

Figure 10: Carolus Chartarius, Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, Print, Book Illustration, British Museum.

Figure 11: Gian Vincenzo Gravina (1664-1718).

The “Arcadia Prima”

The initial period of the institution set the ground for women's participation in its organization and was of primal importance to what would unfold later concerning the prompting of women's literary production. In this regard, the vision of one of its founders, Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, needs a detailed examination. Crescimbeni, the first leader of the Academy, was a historian and literary critic. He founded the Academy with thirteen other prominent Roman literary figures. Among them were Gian Vincenzo Gravina (1664-1718), Pier Jacopo Martello (1665-1727), and Lodovico Antonio Muratori (1672-1750). They were the principal sources for the aesthetic ideals of Italian poetry and music of the Academy. Crescimbeni kept a historical account of the Arcadian Academy, preserving records of the Academy's meetings, discussions, and activities. During Crescimbeni's tenure, membership grew considerably [30], and the institution attempted to cater to the needs of the papacy honoring all European courts equally.

Crescimbeni wanted to provide a venue for teaching and study good taste, so that modern poetry would not inherit the mistakes of their recent predecessors, the Marinist poets. His two most important publications, L'Istoria Della Volgar Poesia (1698) and La Bellezza Della Volgar Poesia (1700), reflect his historical and pedagogical ideas. Both works are among the earliest comprehensive histories of Italian poetry and include brief biographies of Italy's best-known poets and extracts of their works and comments on style and the artistic merits of each author.

Figure 12: Book in Collection of the National Central Library of Rome.

From 1690 until 1720 and under the leadership of Crescimbeni, women's attendance was increased. Elizabetta Graziosi asserts that in Crescimbeni's time as a leader, the Academy selected female figures for "the lessons they could teach, against the excesses of an abusive aristocracy and in favor of a moderate appreciation of the female virtues.” [31] The first women admitted to the academy were part of the powerful elite and had distinguished residences, providing meeting places and organizing literary conversations. The same model of aristocratic women offering their palaces and acting as hosts and organizers was later replicated in all Arcadian colonies [32]. That way, the academy concurrently admitted females in its ranks, especially those believed to have moral character, but also excluded some, those whose behavior was disapproved of by society. This latter group was mainly rejected for their public social behavior concerning lovers or taking second husbands. This way, the academy rewarded compliance with the times' basic social rules and chastised women's rebellion towards them no matter how outstanding their talents would be [33]. Some scholars suspect that Crescimbeni's acceptance of women into the academy acted as an institutional promotional device and a means that he exported and deployed to the colonies [34]. It is also recognized that thanks to Crescimbeni, the progressive inclusion of women in his organization saw first their participation, then their formalized admission, then their recitations, and finally their published texts [35]. One can sense a firm determination of the leader in defying some norms to introduce female participation into a historically male sphere, albeit at the same time also reinforcing some traditional practices, as we stated earlier when censuring immoderate female social behavior.

Women's work suffered further limitations when observing that the Academy produced its own publications in which there seems to be a distinction between the themes and literary forms touched on by male and female Arcadians. During the first 38 years of the history of the Academy, and under the leadership of Giovanni Maria Crescimbeni, 74 women were admitted out of 2,419 members. For almost forty years, the Arcadian Academy advanced and promoted its female affiliates' poetic work, including them in the official publications of the organization. Female members accounted for at least eight percent of the literature printed by the Academy. In nine volumes published between 1716 and 1722, eight percent of the poems printed were by women (20 out of 237), and that accounts for a little over one-quarter of the female membership. The poetic subjects reserved for women were simple affections, while male work included intellectual opinions, strong emotions, and literary operations [36], delineating a narrower operative intellectual field, relegating them to a circumscribed feminized affective, creative realm.

In spite of severe intellectual constraints, the strategies of inclusion of the Academy led to, by the 1730s, numerous women being included in serious bibliographies of Italian writers and some of the famous Italian anthologies of the eighteenth century. As a result, the authors of these new catalogs and literary histories played an important role in advancing and disseminating Italian women's writings [37]. These publications included Giovanni Battista Recanati's Poesie Italiane and Luisa Bergalli's two-volume Componiment Poetici. The latter exclusively published work of women and presented the most exhaustive catalog of their work to date [38]. It included poems, bibliographies, and biographies of over two-hundred female poets whose works dated from the thirteenth to the eighteenth century. In addition to the above-mentioned publications, there were those of Crescimbeni himself, Fontanini, Recanati, Gobbi, and others.

By the end of the 1720s, the academy was reaching the culmination of a period with the aging of the original founding members and ended with the death of Crescimbeni in 1728. His legacy of having provided inclusive opportunities for Italian female writers will forever be inscribed in the history of European women as a whole, as an incipient phase of female involvement in literary creation, a beginning that critically inaugurates the disclosure of their gender's equal intellectual power.

The “Arcadia Seconda”

The second period of the Arcadian Academy history represents a suspended evolution and a fall back into a state of retreat for Italian female writers. The preconceived ideas of the leader who succeeded Crescimbeni after his death resulted in the female literati's marginalization. He actively intercepted their participation in the institution. Between 1728 and 1743, Francesco Maria Lorenzini (1680-1743) was the custode of the Arcadia Academy. He was part of the organization while Crescimbeni was its leader. However, Lorenzini had been a discordant figure who had left the Academy between 1711 and 1718. The nature of the contention was incited by what he perceived to be ruptures of the democratic rules and his predilection for a more robust effort at literacy reform. Lorenzini's tenure had some dire consequences for women poets. He did not particularly cultivate female memberships, calling them the "weak sex." During his tenure, women writers almost disappeared from the academy ranks, and in his fifteen-year mandate, only ten women were nominated as members [39].

Additionally, Lorenzini suspended most of the normal institutional operations focusing its efforts primarily on nurturing the literary elite. No records of activities or members exist, and different membership patterns, meeting locations, and program emphasis were put in place, diminishing considerably the scope of influence of the institution. Besides, during this period, the Academy experienced fewer members' participation, selecting only those the leader considered to have genuine literary interests and talents. All in all, mainly committed young male writers attended the gatherings. They met every Thursday to discuss good literature and to read classical plays at Lorenzini's house, a location that promoted a sense of intimacy. Some of the functions of the Academy established by Crescimbeni were completely eliminated. The Accademia no longer participated in diplomacy for the papal court; there were no special meetings for any elite members, nor did it publish members' work. Just a few individuals were acclaimed. Finally, in 1741, Lorenzini moved to a suburban villa for health reasons, and the weekly Arcadian meetings came to an end. He died in 1743 [40].

Lorenzini reduced the Academy's activities as a whole, but above all, he cast a shadow over the achievements that Italian women had conquered in their participation in cultural and intellectual pursuits.

However, due to the lack of attention given to female members in Rome by Lorenzini, an increase in women's participation in a small Arcadia colony in Parma, a city that housed the Bourbon Court, arose. This was due to the colorful character of Carlo Frugoni, poet and librettist and the founder of the colony in 1738. Frugoni was a great incubator and promoter of poetry as a social practice in which a new image of the female Arcadian would be forged, the public seductive persona of the lyric improviser whose initial appearances originated in Parma [41]. This character would be shaped by public opinion rather than formed by a closed academic world, a distinction favorable to the contrived and regulated female world.

The Arcadia colony meetings in Parma were held on a small island inside the ducal garden, where the nymphs, Arcadians or not, would entertain. They would exchange rhymes, little notes, and jokes that found no place in the literary publishing arena but would entice a large public lover of improvised poetry [42].

The “Arcadia Terza”

This period of the Arcadian Academy represents the recapturing of the vision that Crescimbeni had originated and the most fertile ground for female Italian poets in which the combination of their creativity was enhanced by their improvisational performative excellence. These qualities were the center of attraction for both an internal and external public and one of the outstanding cultural eccentricities that the Grand Tourist was eager to witness.

From 1743 until 1766, Monsignor Michel Giuseppe Morei (1675-1767) assumed the Academy's leadership. During his tenure, he represented all political interests in the membership, particularly among the acclaimed. He reintroduced events that served the Papal court's diplomatic policies, advancing at the same time the most talented poets who had felt neglected in "Arcadia Prima." He also looked after the completion of Bosco Parrasio on the Janiculum hill, a permanent garden for the Arcadian Academy, which had not been used since 1728. Morei's "Arcadia Terza" reinstated regular meetings and the official Arcadian publications.

Michel Giuseppe Morei forged a renewed era of inclusion for women in the academy inspired by what was happening in the colony in Parma, successfully integrating its lessons. Female membership began increasing again. Between 1746 and 1760, it has been calculated that twenty-five percent of its members were female. Michel Giuseppe Morei is credited with building a new image of the literate Italian woman: the professional in improvisation connected to the world of politics and culture that the public yearned to go to see. In this late Arcadia period, the power of the organization and influence grew ever more extensive, emanating from Rome and reaching all confines of Italy and Europe. The Roman salons began proliferating to the point where they were functioning at an international level. As its leader noted, the growing appreciation for improvisation was responsible for "the extremely large audiences that crowded Arcadia when there was improvisational singing.” [43] The most successful improvisers were all women.

Women Improvisers: A Consequence of Academia Terza

This group of women poets' success is an outstanding outcome of the Accademia Degli Arcadi and was pervasive through several decades. They performed impromptu and histrionic live poetry, an art form that was proper to the Italian regions' culture but which female performers of the eighteenth century brought to a new level of excellence and popular demand.

At the time, improvised poetry, a medium already ingrained in Italian history, meant "the talent of declaiming verse extemporaneously and on a subject given (by the public).” [44] Many learned poets began their careers improvising or improvised at some point in their life (Metastasio, Gian Battista Felipe Zappi, Paolo Rolli, Tommaso Crudeli, Carlo Innocenzo Frugoni, Bartolomeo Lorenzi, Aurelio de Giorgi Bertola, Giovanni de Rossi, Giovanni Pindemonte and Vincenzo Monti, just to mention the most prominent) [45].

Figure 13: Francesco Bartolozzi, Anna Piattoli, Portrait of Maria Maddalena Morelli (Corilla Olimpica), after 1740 - before 1760, 4.64” x 5.74”, print, Civic Graphic and Photographic Collections in Civic Collection of Prints Achille Bertarelli, Milan.

The Arcadian Academy played a leading role in how women poets and improvisers achieved notoriety in eighteenth-century Italy. By the second half of that century, women had become the most acclaimed and prominent improvisers in Italy, and they were recognized as outshining their male counterparts. The most prominent among these female poet improvisers were Maria Maddalena Morelli, Teresa Bandettini, and Fortunata Sulgher Fantastici. They either performed solo or in competition with other improvisers. They were very popular and successful and were adulated and acclaimed as cultural treasures when it was still being debated whether or not women had equal intellectual capacities to men. In the Grand Tour era, foreigners were eager to see them perform [46], multiplying their prominence with their interest and making them known abroad. Ugo Foscolo, a paramount literary figure of the times, said: "indeed it appears that the sweetness of women's voices, the mobility of their imagination and the volubility of their tongues, would render extemporaneous poetry better fitted to them than to men.” [47] In other words, their nature was responsible for their abilities, not their intellectual prowess, designating through this judgment, as we will unveil, the Achilles heel by which women would be defeated.

By the end of the century, the accomplishments of women improvisers were subverted by their own exceptional achievements, and the practice was condemned as superficial and irrelevant in the general cultural landscape. Doomed and dammed by their gender roles, what brought them to their success is what, in the end, cemented their bad fortune. Besides, the art form they cultivated was evanescent and left no trace after their presentations were executed [48]. That quality in the long-run brought them to historical obscurity as, after performing, there were no tangible remnants of their artistry left. Moreover, women's predominance in this field was conducive to label the medium to having exclusive female qualities and, as a consequence, doomed it to be seen as marginal and inferior despite being grounded in Italian culture, aesthetics, and values. On this subject, Paola Giuli comments: "It was women's success with this once highly regarded medium that determined patriarchal re-appropriation by devaluation." Remarkably, by the end of the eighteenth-century women improvisers were erased from literary history.

By the end of the century, after the arrival of the French army in Piedmont in the spring of 1796, the intellectual focus of most of the nineteenth century was dominated by the Risorgimento, the political and military struggle for national unity and independence for the Italian peninsula. Literature during this period changed its focus and addressed socio-political issues, and many women worked for the cause of consolidating a greater Italy. After the unification of the Italian peninsula in the second half of the nineteenth century, women resumed creative writing [49].

Physical Remains of the Arcadia Academy

The fleeting quality of the literary production of women improvisers left few traces due to the nature of their art. Nowadays, the most tangible remains of the Arcadian Academy are its own publications, its members’ publications, the anthologies where its members were included, in addition to the Bosco Parrasio [50] and the Consul Smith Library, where many of the books published converged.

The Bosco Parrasio was emblematic of the type of settings where the pastorelles used to perform. The site was constitutive and conducive to the Pastoral mental makeup. The Consul Smith Library is currently located in the British Museum Library in London, and a substantial part of the writings done by the female poets examined in this essay are represented in it. It is recognized as the greatest collection of Italian female writers from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century. This library is a treasure that still needs to be unveiled and brought to light by historians and researchers alike.

Figure 14: Plan of Bosco Parrasio, the headquarters of Accademia dell' Arcadia in Rome, 1804. Source: Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, Storia dell'Accademia degli Arcadi istituita in Roma l'anno 1690.

Figure 15: The Bosco Parrasio in full Arcadian meeting in 1788 (Institut Tessin, Paris), http://www.rennes-le-chateau-archive.com/christine_de_suede_2.htm

Today the Bosco Parrasio gives us a picture of the kind of environments the Arcadians utilized to make their recitations and performances come to life. The transient performative quality of the art of women poet improvisers was channeled and enhanced by the physical environment where they used to perform, and because of its ephemeral nature, no remnants were left behind of the poetry itself. That is one of the most important factors for their historical disappearance.

To deeply understand the universe of the art of improvisation in poetry, we can be aided by analyzing the type of settings in which they used to be exhibited. In Rome, the Bosco Parrasio, conceived inspired by pastoral precepts, is the epitome of the type of physical architectural space where performances were enacted. Before its construction, performances by the Arcadians occurred in garden settings. The Bosco Parrasio was an analogous setting to the one used in Parma by the women improvisers where they began seducing their loving public, where the art form began taking shape. It was built and funded by King John VI of Portugal and designed by architect Antonio Canevari and his pupil Nicola Salvi. It was laid out on the slopes of the Janiculum Hill in Rome [51] and inaugurated in 1726 [52].

These settings were the quintessential type of surroundings conducive to the pastoral ethos where artists were searching in the natural surrounding the inspiration to be transported into the pastoral mental space. The garden, the natural environment, and the Bosco Parrasio were intimately linked to the art of women improvisers and quintessential constituents of their creations as immersive and experiential conceits. Furthermore, the Bosco Parrasio was used to indicate both a physical surrounding and a state of mind, evoking the shepherd-poets' nostalgic simplicity of the mythological Arcadia of classical antiquity. It is a neoclassical building with a concave façade, a staircase, and a small amphitheater—a type of structure historically associated with poetic performance. Behind it, a small building called the serbatoio was constructed and was where the records of the Academy were kept and where meetings could take place in case of bad weather. It is concealed behind the final arcade that contains the backstage of the amphitheater.

Its dramatic open space, created as a stage design with a startling view of the city of Rome, was certainly conducive to the evocative, nostalgic, and reverie-embracing nature of the Arcadians' poetic and musical work. The circular amphitheater speaks of the communal and chimerical nature of the Arcadian gatherings. As Susan Dixon notes, the pastoral fantasy was the foundation of the poets' psyche at Arcadia Academy, and the theater was their medium. The art of the women improvisers threaded a complex set of tools among which was to act as a vehicle between improvised language, singing, performative mastery in collaboration with the garden arrangement (or the architecture of Bosco Parraiso) to transport a communal audience to a specific inspirational mental disposition and mood. None of this could be translated into a film or a documentary, mediums that could have preserved some of their art; hence, the legacy of Italian improvisers disappeared [53].

Despite the outstanding loss mentioned above, a remarkable collection of books written by women authors was assembled by Consul Joseph Smith (1673-1770), the Biblioteca Smithsiana, which he sold to King George III, between 1759 and 1762, under the condition that the library was kept together [54].

The book collection was a real treasure with a surprising prominence of many Italian women writers. In it, some fifty-eight Italian women writers fall into two distinct groups [55]. In the first group are sixteenth and seventeenth-century women writers who are, for the most part, the accepted relevant women writers of the Italian Renaissance. The second group includes thirty-eight women published in the early eighteenth-century anthologies under their names and were edited by Crescimbeni, Gobbi, and Renacati. They all participated in one or more of the Arcadian Academies spread around the Italian regions [56].

The Consul, a rare male advocate of women intellectuals, had kept himself informed regarding the Arcadian Academy activities, taking notice of the female avant-garde literary movement that the Academy had fostered. The Arcadian Academy in Rome and its colonies constitute an essential event that contributed the most to women writers' unprecedented participation in literary venues and their appearance in book catalogs, anthologies, and literary histories as authors in the early decades of the eighteenth century. The purchase of the Consul Smith Library by George III and its entrance from King's Library into the British Museum Library in 1823 ensured that a large body of work by Italian women writers would be available to the public. This outstanding collection of books are still preserved in the museum's library and available for consultation even today. Nonetheless, it is remarkable to observe the vanishing of these celebrated modern Italian women writers' work and their continued evasion from historians. In the Museum's publication of 2009 and titled Libraries within the British Library: The Origins of the British Library's Printed Collections by Giles Mandelbrote and Barry Taylor, particularly the two essays that address the Consul Smith Library, there is no mention of the work by Italian women writers contained in it. In her essay about this library, Diana Robin remarks, "The reception of women writers in national histories has long been variable and unstable, their memory more quickly occluded by time than those of their male compatriots.” [57] In agreement with her, the inclusion of this piece of history in this essay is motivated to highlight the vulnerabilities of women's intellectual pursuits and the importance of the male intellectual backing to safeguard women's insertion into the annals of history. Men have always had the power to either promote female's work or interfere in bringing their value into the cultural realm. Without their support, their work goes into obscurity.

Conclusion

The plight of the eighteenth-century Italian women poets' place in history is marked by men acting as gatekeepers of what they would consider appropriate or not included in the cultural domain. The only exception is Luisa Bergali, who, as a woman, produced the impressive two-volume women anthology Componimenti Poetici (1726) [58].

The history of the Italian women poets of the eighteenth century, as we know it today, was forged first by Giovanni Mario Crescimbeni, who opened the doors to women in the Arcadian Academy, allowing their recitations and their inclusion in publications that endured over time. This fact resulted in remarkable consequences for the history of literature and specifically women's contribution. It is here that the literary women's concept was elaborated and looked at by not only Italy but all of Europe [59]. That triggered their acceptance by society at large, and an essential network of literate women was created, first within Italy and, further in time, within Europe.

Francesco Maria Lorenzini interrupted this development with his complete neglect of women's voices, bringing them into silence for a few decades. Finally, Michel Giuseppe Morei reopened women's opportunities within the Academy and facilitated the enormous success of women improvisers by the second half of the eighteenth century.

Carlo Frugoni should be recognized for his role in the Arcadian Academy of Parma. However, most notably, Consul Joseph Smith should be highlighted for his vision of collecting books by the most important Italian women writers of the first half of the eighteenth century and placing them in one of the most remarkable libraries of the world, otherwise not only the work of the poet improvisers would have been lost, but all the published work would have disappeared as well. As noted by Diana Robin, what remains a mystery is that contemporary men can still perpetrate neglect of women writers' history, a lamentable omission that attests to the continuing idea that women's intellectual value is not equal to men.

All the historical accounts described in the present essay reveal an out-of-the-ordinary history of Italian female writers, Italian women, and women in general. It describes the struggle of a gender that was always looking for openings in the system to be able to exercise their full humanity, letting the expression of their intellect and their creative mind burgeon with whatever little space or breath was being given to them. It is an inspiring and touching history that deserves the attention of a larger audience. It represents a proto-modern laboratory of push and pulls always under the umbrella of the male gaze, judgement, and constraints.

Notes

[1] Italian Regions: are called so when the Italian peninsula was a conglomeration of different states each with their own particularities and when Italy was not unified country.

[2] Today housed at the British Library in London.

[3] Paula Findlen, Catherine M. Sama and Wendy Wassyng Roworth, Italy’s Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009), 113.

[4] Rinaldina Russel, Italian Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook (Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1994), XVII.

[5] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XVII – XVIII.

[6] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XVII – XVIII.

[7] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XVIII.

[8] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XVII.

[9] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XIX.

[10] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XX.

[11] Virginia Cox, Lyric Poetry by Women of the Italian Renaissance (Baltomire: JHU Press, 2013), 35.

[12] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XXI.

[13] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XIX.

[14] Paula Findlen, Catherine M. Sama, Wendy Wassyng Roworth. Italy’s Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009, 5.

[15] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 17.

[16] As noted by Roberto Bizzocchi in his book “A Lady’s Man,” cicisbeism, an eighteenth-century phenomenon in Italy, did not mean adultery. It was an officially accepted custom realized openly with the husband’s consent. The cicisbeo or escort would accompany the married woman to assist her in all her activities.

[17] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 17.

[18] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 17.

[19] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 60.[20] Richard Jenkyns, “Virgil and Arcadia,” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 79 (1989): 27.

[20] Richard Jenkyns, “Virgil and Arcadia,” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 79 (1989): 27.

[21] Vernon Hyde Minor, “Ideology and Interpretation in Rome's Parrasian Grove: The Arcadian Garden and Taste,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome Vol. 46 (2001): 183-228.

[22] Susan Dixon, “Women in Arcadia,” Eighteenth Century Studies, Vol. 32, Nº 3, (Spring 1999): 375.

[23] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 114-115.

[24] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 107.

[25] Dixon, “Women in Arcadia,” 371-372.

[26] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 108.

[27] Dixon, “Women in Arcadia,” 372.

[28] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 111.

[29] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 64-65.

[30] Dixon, “Women in Arcadia,” 372.

[31] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 113.

[32] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 111-112.

[33] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 111-113.

[34] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 115.

[35] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 115.

[36] Dixon, “Women in Arcadia,” 373.

[37] Diana Robin, “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers in Early Modern Britain,” Early Modern Women, Vol 6 (Fall 2011): 56-57.

[38] Robin, “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers in Early Modern Britain,” 57.

[39] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 116-117.

[40] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 116-117.

[41] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 117-118.

[42] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 117.

[43] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 319.

[44] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 304.

[45] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 304.

[46] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 304-305.

[47] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 305.

[48] Findlen et al., Italy’s Eighteenth Century, 307.

[49] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XXIII.

[50] The architecture and garden of Bosco Parrasio allude to the original Greek Arcadia and is a distinct type of strictly symmetrical design, consisting of equal parts architecture and landscaping. It has a receiving arcade that served as a threshold into which an out of this world kind of environment would be offered to an audience: a place to go dreaming. Two ascending ante areas succeed the entry with three landing areas before reaching the climatic rear end. It is a place where nature is encroached in a civilized environment. The presence of a common feature in the architecture of the time, the stair, occupies a prominent position. It is a transitional piece of construction split in two mirrored parts with several landings culminating in the round arena devised for the Arcadians’ readings and performances. The Bosco Parrasio was built in Rome as a permanent garden for the Arcadian Academy. It still exists today and is a remarkable construction that stands as a physical legacy of the Arcadian Academy and as an icon of the translation of the pastoral ideals into an architectural and landscape enclosure.

[51] Susan Dixon, “Vasi, Piranesi and the Accademia degli Arcadi: Toward a Definition of Arcadism in the Visual Arts,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 61 (2016): 224.

[52] Minor, “Ideology and Interpretation,” 183-228.

[53] Dixon, “Vasi, Piranesi and the Accademia degli Arcadi,” 224.

[54] Consul Joseph Smith (1673-1770) settled in Venice in 1700 and was appointed as the British Consul there from 1744 until 1760. In 1720, Smith began an extensive collection of rare books in addition to a remarkable art collection. In 1755, a 900-page library catalog of his collection, the Bibliotheca Smithsiana, was published by Giambattista Pasquali, one of the three most important Venetian publishers of the period. Owing to the market collapse in the mid-1750s, Smith was forced to find a buyer for his books. King George III finally acquired them in a deal closed between April 1759 and July 1762, with the condition that the library would be kept together.

[55] Robin, “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers,” 44.

[56] Robin, “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers,” 59.

[57] Robin, “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers,” 43.

[58] Russell, Italian Women Writers, 56.

[59] Russell, Italian Women Writers, XXI.

Bibliography

Bizzochi, Roberto. A Lady’s Man: The Cicisbei, Private Morals and National Identity in Italy. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Cox, Virginia. Lyric Poetry by Women of the Italian Renaissance. Baltimore: JHU Press, 2013.

Findlen, Paula, Catherine M. Sama, Wendy Wassyng Roworth. Italy’s Eighteenth Century: Gender and Culture in the Age of the Grand Tour. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Dixon, Susan. Between the Real and the Ideal: The Accademia Degli Arcadi and its Garden on Eighteenth Century Rome. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2010.

Dixon, Susan. “Women in Arcadia.” Eighteenth Century Studies, Vol. 32, Nº 3, (Spring 1999): 371-375. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30053912.

Dixon, Susan. “Vasi, Piranesi and the Accademia degli Arcadi: Toward a Definition of Arcadism in the Visual Arts.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 61 (2016): 219-262.

Green, Karen. A History of Women’s Political Thought in Europe, 1700-1800. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

Hyde Minor, Vernon. Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Incorporated, 1999.

Hyde Minor, Vernon. The Death of the Baroque and the Rhetoric of Good Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Hyde Minor, Vernon. “Ideology and Interpretation in Rome's Parrhasian Grove: The Arcadian Garden and Taste.” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, Vol. 46 (2001): 183-228. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4238785 Accessed: 25-08-2019 04:12 UTC

Lehner L., Ulrich. Women. Enlightment and Catholocism: ATransnational Biographical History. London: Routledge, 2017.

Jenkyns, Richard. “Virgil and Arcadia.” The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 79 (1989): 26-39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/301178.

Messbarger, Rebecca. The Century of Women: Representations of Women in Eighteenth-Century Italian Public Discourse. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002.

Messbarger, Rebecca: Paula Findlen. The Conquest for Knowledge: Debates over Women’s Learning in Eighteenth-Century Italy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005.

Messbarger, Rebecca, Christopher M. S. Johns, Philip Gavitt. Benedict XIV and the EnlightmentL Art, Science and Spirituality. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Robin, Diana. “The Canonization of Italian Women Writers in Early Modern Britain.” Early Modern Women, Vol 6 (Fall 2011): 43-78. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23617326.

Russel, Rinaldina. Italian Women Writers: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1994.